Donald Trump Jr. took the stand Wednesday to testify in the non-jury civil trial stemming from New York Attorney General Letitia James’ lawsuit against the Trump family and Trump Organization.

The former president’s eldest son, who is listed as a defendant in James’ lawsuit, took the stand Wednesday afternoon in a Manhattan courthouse.

Donald Trump Jr., an executive vice president at the Trump Organization, testified that he does not have professional training with generally accepted accounting principles, and instead, relied on accountants with regard to financial statements at the Trump Organization.

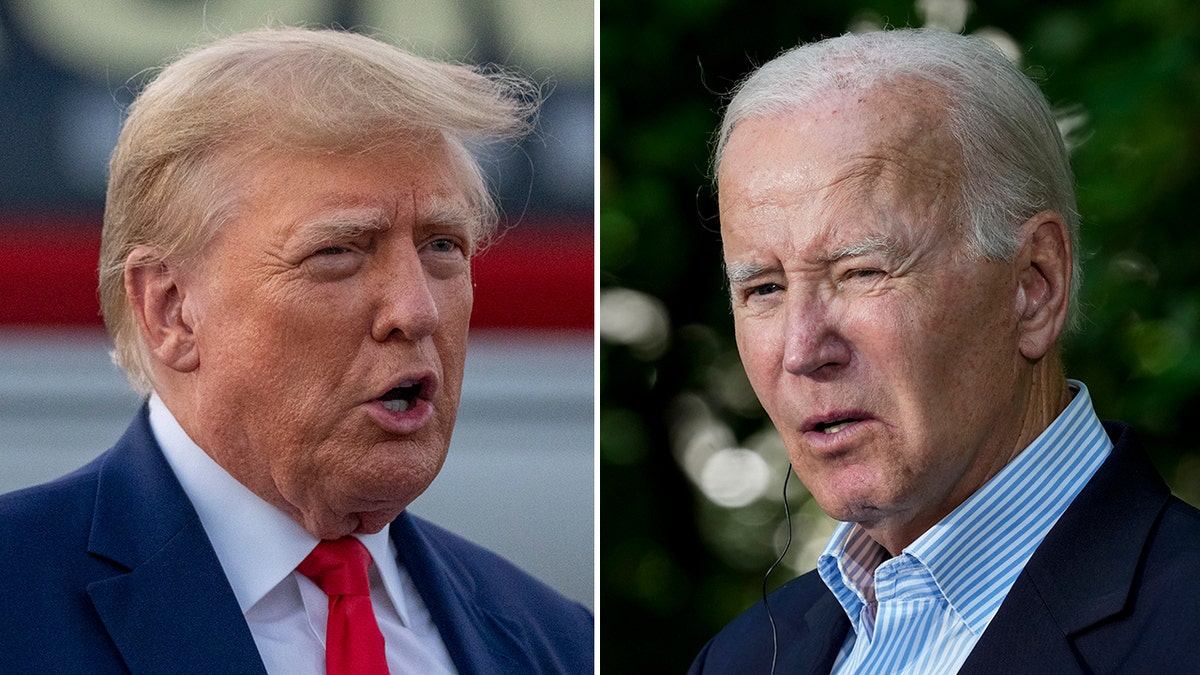

The lawsuit centers on whether the former president and his business misled banks and insurers by inflating his net worth on financial statements.

He also testified that he reported to former Trump Organization Chief Financial Officer Allen Weisselberg for a short time, and later reported to his father until he became president of the United States.

Donald Trump Jr. testified that his father did not make any business decisions while he was in the White House.

Eric Trump is expected to testify next in the trial.

NEW YORK JUDGE FINES TRUMP $10K FOR VIOLATING PARTIAL GAG ORDER IN CIVIL FRAUD TRIAL

Ivanka Trump was dismissed as a defendant from the case over the summer after a decision by a New York Appeals Court, but she was set to appear for testimony. Her attorneys on Wednesday, though, filed a notice of appeal to the decision requiring her to testify at her father’s civil fraud trial.

Donald Trump Jr. speaks to audience members before introducing U.S. Senate candidate Rep. Ted Budd (R-NC) during a campaign rally at Illuminating Technologies on October 13, 2022 in Greensboro, North Carolina. (Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images)

Former President Trump, Don Jr., and Eric Trump are all still listed as defendants.

The trial comes after James, a Democrat, brought a lawsuit against Trump last year alleging he and his company misled banks and others about the value of his assets. James claimed Donald Jr., Ivanka, and Eric, as well as his associates and businesses, committed “numerous acts of fraud and misrepresentation” on their financial statements.

The appellate ruling from over the summer, which limited dismissed Ivanka Trump as a defendant, also prevented James from suing for alleged transactions that occurred before July 13, 2014, or Feb. 6, 2016, depending on the defendant.

Eric Trump arrives at New York Supreme Court, Monday, Oct. 2, 2023, in New York. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Trump has blasted James for bringing the lawsuit; for the trial not having a jury; and Judge Arthur Engoron, presiding over the trial, calling him “corrupt.”

JUDGE DENIES TRUMP TEAM’S REQUESTS FOR IMMEDIATE VERDICT IN FRAUD TRIAL AFTER COHEN TESTIMONY

“The Attorney General filed this case under a consumer protection statute that denies the right to a jury,” a Trump spokesperson said. “There was never an option to choose a jury trial. It is unfortunate that a jury won’t be able to hear how absurd the merits of this case are and conclude no wrongdoing ever happened.”

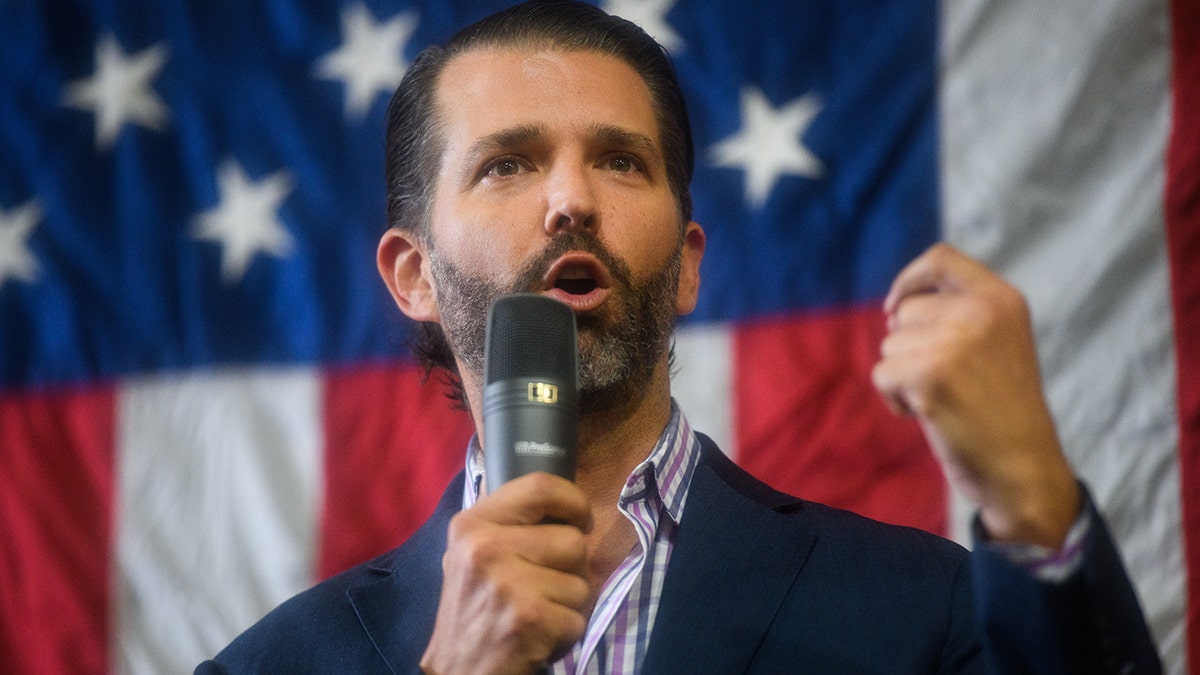

President Donald Trump and daughter Senior Advisor Ivanka Trump make their way to board Air Force One before departing from Dobbins Air Reserve Base in Marietta, Georgia on Jan. 4, 2021. (MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images)

Engoron, last month, ruled that Trump and the Trump Organization committed fraud while building his real estate empire by deceiving banks, insurers and others by overvaluing his assets and exaggerating his net worth on paperwork used in making deals and securing financing.

Engoron’s ruling came after James sued Trump, his children and the Trump Organization, alleging that the former president “inflated his net worth by billions of dollars,” and said his children helped him to do so.

This is a developing story. Please check back for updates.

Fox News’ Maria Paronich contributed to this report.